Legacy

Guest author Lindsay Johnstone reflects on a house, a family, and two trees—140 years of history intertwined. What happens when the trees are cut down?

Words and images: Lindsay Johnstone

A decade ago—save a week—we drew up outside our new home, the impractical three-door car low on its wheels with valuables we couldn’t trust to the movers. Valuables that included our 16-week-old daughter. The cat. The wedding album. A print gifted at that wedding, framed behind the thinnest of glass. “Let Your Boat of Life be Light”, it said.

Our “boat” felt anything but.

That evening, we avoided the boxes. Sat instead eating fish and chips on our front lawn, catching the last of the sun as it peeped out momentarily between trees and hedge to illuminate the budding bluebells growing in clusters across the grass. I swapped the remnants of dinner for my daughter, patting her cloth-nappied bum as she settled. I fixed my attention on the low-hanging branches of the pair of trees that stood sentinel a few metres away. Some weeping variety I couldn’t then name and which were still bare that April evening. I glanced around; my untrained horticultural eye taking in familiar markers of the season. Yellow gorse. Cherry blossom.

Our gorse. Our blossom.

There would be a lot to learn about this garden, this house. We were “home” though it would take some time before it really felt like it.

Today is a Thursday. I’ve returned from the bus stop more harried than I’d like. My doing: a need for photographs. Not because this date held any particular significance but because it was the last time my daughters would see those two gnarly guards standing tall before our home.

“Bye trees!” shouted my younger daughter after she’d unwrapped her arms from around one of them. “You’ve had a good life!”

And, for the most part, they had.

It takes three tree surgeons a matter of hours to reduce them to a pile of firewood. As the clear-up nears its end, I look at a view I’ve never seen before, wondering when in the past hundred or so years the house was last this exposed. A neighbour passes by. “It’s always so sad when trees have to go,” she says. Part of me needs to make clear we wouldn’t chop them down unless it was unavoidable. We’d always spoken about being custodians of this house; never thought it ours to do with as we pleased.

We’d noticed the trees weren’t behaving a few years ago. Even later to bud, we wondered if it was a consequence of the climate emergency or something benign to do with their growth cycle. Then we noticed the bulbous trunks, thickening with growths. Maybe they’d always been like this? We’d been busy with the babies and the task of breathing new life into the old house. Then during my daily walk around the park last winter, I arrived at a diagnosis. Similar trees had been condemned by the Council: victims to savage southern spores that destroyed them from the inside out. A month or so passed and the last of the gales ripped yet more sorry branches for us to gather come morning. They were becoming a liability. What if they fell on the house in the next storm? What did the insurance documents say?

We booked the tree surgeons.

Last night, I stood at our bedroom window looking over the highest branches. The trees meant home to me. Home, too, to the long-tailed tits I could see hopping from branch to branch pecking at the tiniest insects. I pulled the curtains shut on them for the last time.

In the afternoon, I wander over to one of the stumps. “God, it stinks!” I say, vindicated. I imagine the roots radiating like an invisible mirror of the branches that used to shade me. How far do they run? I hunker down and embark on the task of counting the rings.

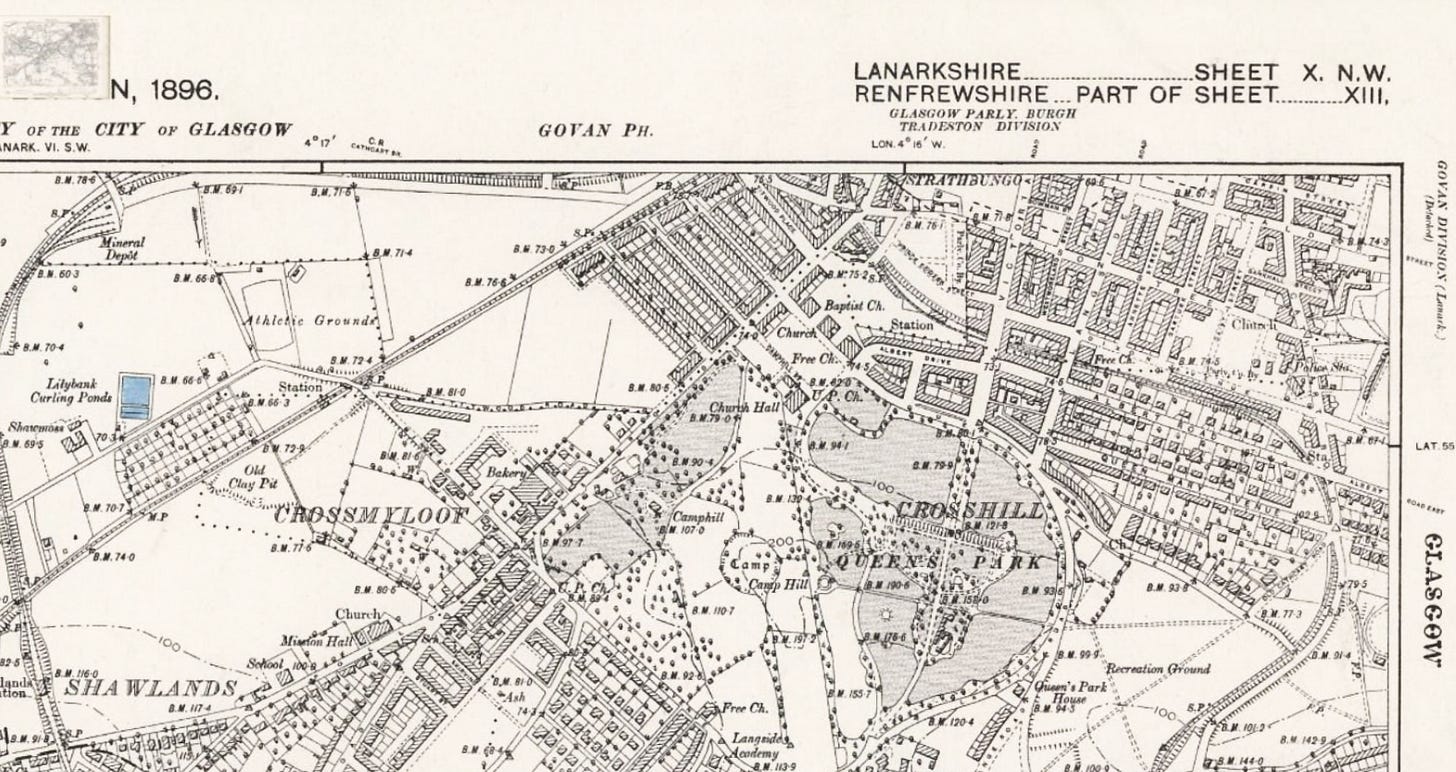

“About 140,” I say, eventually. Planted in the 1880s. The Lowther era.

I contemplate afresh everything these trees must have stood over. When we first moved in, I’d been consumed with finding out as much as I could about the house’s former inhabitants; any interest in my own family tree replaced with the desire to breathe life into the stories of strangers. I lost hours forming meaning from census and valuation rolls I’d scoured the internet to find, and it’s that sheaf of papers I get up to look for now; the disorganised, tea-stained pile eventually located under a pile of New Scientist magazines. “Climate Slowdown: Is It Time to Stop Worrying about Global Warming?” reads one from December 2016. I leaf through the sheets again, looking for Lowther. The family I’d learned the most about.

Richard, his wife Helen and their four children moved into Douglas Cottage in 1882 and were the third family to occupy the house following its completion in 1863. They re-christened it Sutherland House and installed a new frosted glass panel in the front door etched with the Sutherland crest which is still our front door today. I walk to the bay window and look over at the dank stumps and the pale sawdust that surrounds them. I picture them as fragile saplings no taller than the surrounding shrubbery in what would have been a fledgling garden. Did Richard enlist the help of his elder sons to plant them? Might the family have envisaged the trees growing as they did; their planting imbued with the significance of new beginnings? I’ll never know, but that’s never stopped me from fancying.

I return to the papers.

Their youngest son, Peter, was just two months old when they moved from a nearby tenement flat at the long-demolished address of 3 Cathkin Terrace and I imagine afresh the hope and expectation that would have accompanied the move. It’s a feeling I’d had, too, placing irrational faith in a new home as protector. As refuge. I remember the fizzing anticipation as moving day approached. I’d take my chances between feeds to pack another box, wondering how the stuff from our wee flat would work in a house we’d visited only once, in the dark. More importantly, I resolved that what the long-quiet house really needed after being home to an elderly widower was to be once again filled with the chaos of family life. I didn’t know about the Lowthers then. Didn’t know that my hands would soon happen upon information I can still recall the clout of.

My baby had been sleeping when an online search turned up two death certificates issued to the Lowthers in brutal succession. First baby Peter and then his father four years later. This house hadn’t cosseted them from the bitter blows so often dealt to families living in Victorian Glasgow. Superstitiously, I crept in to hover a hand over her chest to check she was still drawing breath. Of course she was and I felt a fool. For this and for having invested in the fantasy that a house and garden had the power to insulate its inhabitants from insidious dangers lurking beyond or breeding—fatally—within. This was an irrational sadness. A sense of loss that was not my own. I appealed to my rational mind. Yes, there were parallels but we lived in different times, surely?

It would take COVID to rattle my foundations so strongly again. The democratising nature of the virus meant the unvoiced fears that oftentimes kept me from my sleep became suddenly socially understood. We had forgotten we lived with only an illusion of certainty about our life chances.

So, what for the Lowthers? Just a typical family of that era, inured to loss. Helen died at home of a cerebral haemorrhage in early 1915, aged 76, alone. Her three surviving children, the hired help and the lodgers we’d discovered in the records were all long gone by then. It would soon be time for another family to call this house home. To tend this garden. Those trees. Did they move into a dead widow’s house thinking they, too, would bring it back to life?

“Come and sit on the bench!”

I put the papers down and check my watch. There’s a wee sliver of time before I need to walk to the bus. Time enough to sit on our “new” bench. Feel the early spring sun on our faces now the trees no longer block it, rough bark now beneath our fingers.

“See!” my husband says, “two perfect seats!” He’s tickled at noticing these divots as he rolled the trunk into position.

I rest my back on the cool blonde sandstone and we are quiet; lost in our own thoughts. Mine? On all that’s come before and the unknowable future that lies ahead. Today, we have witnessed an ending of sorts. But also, I must believe, a beginning. Or if that’s a stretch, a continuation of this house’s story. Ours, too.

“What will our two say when they see the front garden in its new state?” I wonder, gathering myself to go.

“Absolutely nothing,” he replies. “Now, if we’d chopped down the swings…”

So much of this resonated! A really touching piece. A few years ago we had to have a diseased copper beech cut down, it was about the same age as the house (c.1920) and it felt like I was fracturing something. We planted a sliver birch in its place so maybe that will be there for some future family.

This is so wonderful and how I feel about home. I love that the felling of the trees isn’t just a loss, it’s a renewal and a letting in of the light.